"I'm Popeye the Sailor Man

I'm Popeye the Sailor Man

I'm strong to the "finich"

'cause I eats me spinach

I'm Popeye the Sailor Man"

Popeye was the creation of E.C. Segar. The "one-eyed runt" debuted as a minor character in an early comic strip entitled Thimble Theater on December 19, 1919. When Popeye became popular, the comic strip was retitled Popeye. Syndication rights were sold to King Features Syndicate, which debuted the Popeye strip on January 17, 1929, introducing the character to a national audience.

In 1933, the Fleischer Brothers--Max and Dave--adapted the newspaper comic strip character into cartoon shorts for Paramount Pictures. All but three of their cartoons were six to eight minute, one-reelers filmed in black and white. Their three masterpieces were twenty minute, two-reelers filmed in Technicolor: Popeye Meets Sinbad (sic) in 1936, Popeye Meets Ali Baba (sic) in 1937, and Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp in 1939.

The cartoon Popeye muttered and mangled the English language much to the annoyance of English teachers everywhere. He was odd-looking and unsophisticated, but he had a heart of gold with compassion for the underdog. Popeye was brave, chivalrous, and loyal. His pipe could be used as a steam whistle for his trademark "toot-toot." He displayed his ingenuity using his pipe for a cutting torch, a jet engine, a propeller, and a periscope.

The not so secret source of Popeye's great strength was spinach. The spinach-growing community of Crystal, Texas, erected a statue of Popeye in recognition of his positive effects on the spinach industry as a great source of "strenkth and vitaliky."

Several key characters in the Popeye cartoons were based on real people from Chester, Illinois, who made an impression on animator E.C. Segar when he worked there as a reporter. Popeye was based on Frank "Rocky" Fiegel, who in real life had a prominent chin, sinewy physique, a pipe, and a history of fist-fighting in the local travern.

The inspiration for Olive Oyl was Dora Paskel, an uncommonly tall, lanky lady with a washboard figure who wore her hair in a tight bun close to her neckline. She ran the general store.

The Wimpy character was modeled after a rotund, local opera house owner named Wiebusch, who regularly sent his stagehand to buy hamburgers for him between performances.

The Chester, Illinois Chamber of Commerce built a Popeye character trail through their town in honor of E.C. Segar and his creations. Statues of many of the series characters adorn their city streets.

Paramount Pictures sold their Popeye cartoon television rights and their interests in the Popeye brand to Associated Artists Productions (AAP) in1955. AAP churned out 220 new cartoons in the next two years to round out their cartoon package. These made-for-TV cartoons were streamlined and simplified for smaller TV budgets. In short, they were cheaply made.

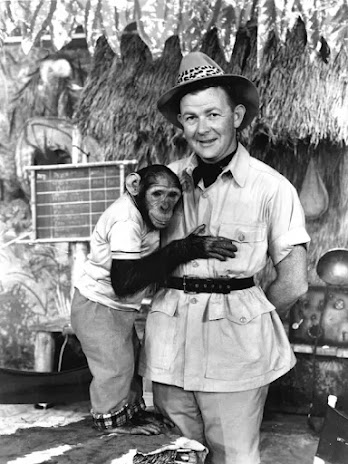

In 1957, CKLW-TV (Channel 9) in Windsor, Ontario purchased the broadcast rights from AAP for 234 Popeye cartoons. The station hired Toby David in 1958 to portray Captain Jolly as the weekday program host. The Captain spoke English with a bad German accent and referred to the kids in his audience as his "Chip Mates." He wore a captain's hat cockeyed on his head, a striped tee-shirt, eyeglasses down his nose, and a signature chin strap beard. The show aired weekdays and weekends from 6:00 pm to 6:30 pm sponsored by Vernor's Ginger Ale.

In character, Captain Jolly was a frequent visitor of hospitalized

children at Children's Hospital in Windsor, Ontario, and he did charity work

throughout the Detroit area as well. Toby David often volunteered his time for St. Jude Children's Research Hospital--his favorite charity.

The weekend hosting chores were handled by Captain Jolly's first mate Poopdeck Paul portrayed by CKLW-TV weatherman Paul Allan Schultz. Poopdeck Paul wore a dark sweater with sleeves rolled up to reveal fake mariners tattoos on his forearms. He wore a canvas sailor's cap confidently tilted on his head.

Schultz's son Bill recalls, "The name Poopdeck Paul came pretty much out of nowhere. Ten minutes before the weekend show went on the air, the program director asked, 'What are you going to call yourself?' My dad thought for a couple of minutes and came up with the name."

That story may be true, but it is also true that Popeye's long-lost father who deserted him on Goon Island was named Poopdeck Pappy. Perhaps the name surfaced in Schultz's subconscious mind.

Captain Jolly used hand puppets for his show which was common for kid's shows of that era. Schultz's weekend show was hipper than Captain Jolly's weekday show. Poopdeck Paul appealed to the older kids in the audience. When the Limbo became a popular dance in 1961, Poopdeck held Limbo contests with his studio audience. When the Beatles' popularity broke across the nation in February 1964, he had kids with mop-top haircuts lip synch Beatles songs live on the air.

When the weather permitted, Poopdeck Paul occasionally did his show on the front lawn outside the CKLW studios. He would conduct go-cart races, miniature golf contests, Hula-Hoop competitions, Frisbee tosses, and relay races with teams made up from his studio audience. Both Popeye co-hosts were popular with kids on both sides of the Detroit River.

CKLW-TV cancelled Popeye and His Pals in December of 1964 after seven seasons, due to programming changes. Toby David took it pretty hard. He continued to work around Detroit doing media work and serving on the board of directors for several non-profit organizations assisting with fund-raising.

In 1971, Mr. David had it with winter in Detroit and retired to Scottsdale, Arizona. For a time, he sold real estate and was a tour guide on the side, but he never lost his desire to entertain. On September 14, 1994 while performing for senior citizens at a Mesa, Arizona senior center, Toby David died from a heart attack at the age of eighty. He was survived by his wife, two sons, and a daughter.

Paul Allan Schultz soured on show business after Popeye and His Pals was cancelled. He became a salesman for many years and had a couple of brushes with the law. For a time he lived in the Netherlands and Thailand. Schultz spent the last six months of his life in Leamington, Ontario, on the Canadian shores of Lake Erie. He died on September 19, 2000 at the age of seventy-five.

As per Schultze's final request, no funeral or burial service was held. His ashes were scattered in an undisclosed Canadian location. Schultz was survived by two daughters and a son. A second son, Bruce, preceeded his father in death. Schultz's daughter Diane told a Windsor Star reporter upon the passing of her father, "He taught us kids never be a spectator; always be a player."