| |||

| Bill Bonds WXYZ-TV Ratings Leader | |

"It's hard being Bill Bonds. You can't even imagine."--Bill Bonds

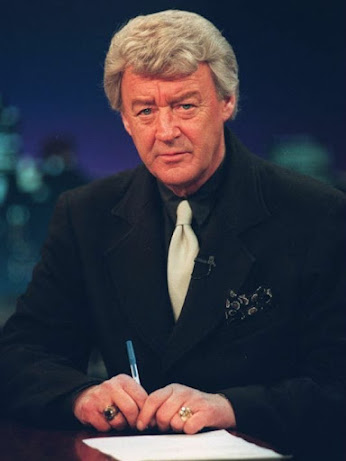

No other Detroit television news celebrity had more written about his every move and misstep than Detroit-born William Duane Bonds, better known as Bill Bonds. He was usually the number one news anchor in the Detroit media market for most of the 1970s, 1980s, and into the mid-1990s. Every point in the Arbitron and Neilsen rating television system translates into how many viewers a show attracts measured against its competition. Millions of dollars of advertising revenue is at stake. Over the years, Bonds was a cash cow for WXYZ-TV.

Bonds had a serious demeanor and expressive face on camera. A lowered eyebrow or a furrowed forehead spoke volumes about how Bill personally felt about the story he was reporting. What made Bonds literally stand out more on the screen than his cross town competition was he wanted to appear as big as possible for the home audience. His face and shoulders, including his fabled toupees, filled most of the screen. When he looked into the camera, viewers felt like he was looking back at them.

After a Detroit Free Press reader poll in 1973 voted Bonds Detroit's Number One celebrity, Free Press staff writer Gary Blonston damned him with faint praise, "Bonds might not be the best newsman in town or even the best voice, but he certainly is the best theater in town. That explains much of why so many people are buying Bonds. He seems to be frequently overplaying the part of a television anchorman, except he really is one."

Over the years, Bonds had a love/hate relationship with the local press. Afterall, the free publicity is what kept his name in the news. Bonds has been described as flamboyant, pompous, arrogant, opinionated, insufferable, tart-tongued, and hot-tempered. Bonds has also earned himself many names like the Babe Ruth of Bombast, the Mad Prophet of the Airwaves, Emperor Bonds, Mr. News Christ, Billzilla, Infotainer, helmet head, scalp-weasel, rogue journalist, and the Sun King of Detroit News.

***

Billy Bonds was born in Detroit in the middle of a Michigan winter on February 23, 1932 during the depths of the Great Depression. He was the second of six children of Richard Bonds and Katherine Collins. What we know of Bill's childhood comes mostly from Bonds himself in a newspaper interview he did with Free Press feature writer Patty LaNoue Stearns in December of 1992 when he was sixty years old.

"I had a marvelous, loving childhood, thanks to my mother, Katherine, a bright caring Catholic homemaker. But I came from a very, very alcoholic family. My Scotts-Irish father was aggressive and domineering. My older brother Dick had a privileged relationship with him."

Bonds went on to describe an incident when he was in the first grade. "My dog got out and was hit by a car. My dad didn't want it in the house, so he put it on the porch in the dead of winter, and it froze to death. In the morning, he told me to throw the dog in the garbage. I was angry at my dad and with shovel in hand, I told him 'It's my dog. I'm going to bury it!' Standing up to my father empowered me and I liked it." This episode may be responsible for Bill's lifelong defiance of authority which marked much of his career.

Bonds grew up to be a rebellious student who was bored with his parochial education. He was encouraged to leave Catholic Central High school, then Royal Oak Shrine, followed by Berkley High School, and finally he dropped out of Royal Oak High School to join the United States Air Force and serve in Korea. While serving his country, Bonds passed his high school equalivancy test. When his enlistment was up, he used his G.I. Bill benefit to enroll at the University of Detroit, majored in political science, and graduated in 1960.

***

Bill Bonds' first broadcasting job was in Albion, Michigan at WALM-AM. He was paid one dollar an hour as a field reporter. From that modest beginning, Bonds followed opportunity and the road back home to Detroit to work at several local AM radio stations before landing a job in 1964 as on-air talent at the WXYZ-TV Channel 7 news department.

Within a year, Bonds was given an anchor position on a program that bore his name--Bill Bonds News. The fifteen minute color broadcast covered news, sports, and weather at 6:30 PM and 11:00PM. During the Detroit Riots of July 1967, the Channel 7 coverage was far superior to Channel 4 or Channel 2's coverage.

Detroit Free Press media reporter Bettelou Peterson lauded the WXYZ-TV news team for their in-the-field coverage, "(They) outdistanced the other stations as the best TV news reporting in Detroit. Bonds' face was particularly expressive as he came back on camera after watching film clips that were broadcast as fast as the film could be developed and sent to the newsroom in real time, each time delivering a small editorial reflecting his feelings." During that terrible week, Metropolitan Detroiters were riveted to their televisions. Bill Bonds became a certified news celebrity.

In 1970, an anchor position opened up at KABC-TV in Los Angeles. Sensing this was a good career move, Bonds interviewed for the position and was hired. He worked there for two years before returning to Detroit. For some reason, the Bonds magic did not work in California's largest media market.

While in tinsel town, Bonds landed bit parts in two Hollywood productions. First in the TV show It Takes a Thief with Robert Wagner in 1970 and the following year in Escape from Planet of the Apes. In both instances, he played a TV news reporter which was not much of a stretch for him. Bonds was released from his KABC-TV contact in February 1971. He did not do well in the Los Angeles ratings and the station decided to go in a different direction.

Two months later, Bonds returned to WXYZ-TV Channel 7. In an interview with Detroit Free Press gossip columnist Bob Talbert, Bonds revealed what his problem in Los Angeles was, "They wanted happy news with the anchors laughing it up. I believe news should be serious and informative. Yakety-yak happy talk on camera did not come easy for me."

In the two years since Bonds had jumped ship, Channel 7 news ratings faltered. WXYZ station manager Donald F. Keck lauded Bonds for his "performance and personal involvement in the Detoit community. Bill's presence will greatly enhance our overall news image and competitive position in our market." Keck noted that WXYZ-TV's news approach will shift from a "light" news style used by their competitors in favor of a more "hard-hitting" approach.

In his gossip column, Bob Talbert broke down Bonds contract for his readers, "Bill Bonds landed a $50,000 a year contact for anchoring their 6:00 PM and 11:00 PM newscasts. His primary responsibility is to boost WXYZ-TV's ratings."

***

With Bonds' return to WXYZ-TV, the station aggressively expanded its news department to make it more competitive in their television news market. Their news programs were expanded and renamed Channel 7 Action News and given a new on-screen look. The musical introduction was the same news theme that the ABC network used in its four other mega media markets: New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago.

The music was an expanded version of a brief melody taken from the movie score of Cool Hand Luke written by Lalo Schifrin for the famous tar-spreading scene. The musical interlude had a teletype-sounding melody that commanded viewers' attention. Following the lead-in, Bonds welcomed his audience and began reading the teleprompter. WXYZ's ratings began to slowly rise.

Channel 7 raided on-air talent from Detroit's other news organizations. From Channel 2, they lured Marilyn Turner to do the weather segment, and to balance Bonds' hard edge, amicable John Kelly was brought in to co-anchor the newsdesk. For sports, Dave Diles continued his segment until he decided to leave the station over a personal issue. That left an opening for Channel 7 to bring in Al Ackerman from Channel 4, who had just been fired for editorializing on the air, something Channel 7 encouraged. The advertising department began running ads proclaiming "We Got Who You Wanted." Their persistence paid off. Within two years, Channel 7 Action News was the top-rated news station in Detroit.

***

Bill Bonds' triumphant return to his hometown was marred by an incident which foreshadowed what would ultimately end his career. Early Sunday morning on November 18, 1973, Bonds, his brother, and their wives were returning home after dining at a West Bloomfield restaurant. Bonds (41) told police that his car was sideswiped by Kenneth Moody (18) of Milford, Michigan, before Bonds' car lost control and went into a ditch. Bonds yelled at Moody and a fistfight ensued. Neither Bonds nor Moody, a student at Michigan State University, filed assault charges. Moody received a ticket for reckless driving. Bonds called a tow truck.

WXYZ-TV spokesperson told the press that Bonds was "a little shook up, and he aches a little, but other than that, he is fine." Bonds was sidelined from his anchorman position for a week to recover from the beating he took. He was taken to William Beaumont Hospital where he was treated for bruises, a swollen eye, and a possible hairline fracture of his cheekbone.

In January 1974, WNBC-TV in New York was shopping for a new anchorman. WXYZ offered Bonds a $75,000 contract to keep him in Detroit. Afterward, the Action News team scored their highest ratings to date, but to his station's chagrin, Bonds was arrested in West Bloomfield Township for drunk driving, littering, and driving without a license on May 5, 1974.

After a patrolman witnessed Bonds throwing a paper cup from his car into the street, he was stopped. Corporal Dan Pitsos determined that Bonds was drinking in his car and drunk. When asked Bonds to show his driver's license, he could not produce it. Bonds was taken to the Oakland County Jail in Pontiac and was held for six hours until his wife Joanne posted a $100 bond.

Bonds was charged with drunk driving and littering, but the charge of failing to carry his license was dropped. WXYZ-TV spokesperson Phil Nye refused to say whether the station would take disciplinary action against Bonds if convicted. Reaction from viewers about Bonds was mostly supportive and favorable.

Bonds pleaded guilty on October 8, 1974 to a reduced charge of driving with visibility impaired "due to the consumption of intoxicating liquor." He was ordered to enroll in Oakland County's Alcohol-Highway Safety Program. Under the reduced charge, the conviction would remain on Bond's driving record for seven years rather than life, and he received four bad-driving points instead of six. Bonds also had to surrender his license plates for thirty days. Because he refused to take a police breathalyzer test, his driving privilege was suspended for ninety days.

WXYZ-TV general manager Jim Osborne announced that because this was Bonds' first offense, the station planned no disciplinary action, but in January 1975, Jac LeGoff from Channel 2 News jumped stations and slid into Bonds' primetime co-anchor spot at 6:00 PM, cutting Bonds back to the 7:00 PM and 11:00 PM News.

By the end of the month, Bonds suffered a mild heart attack while on a business trip to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida. Only the week before, he had recovered from the flu at Bennett Community Hospital. Bonds took a leave of absence to recover his health and returned to Channel 7 on May 5, 1975 to anchor the 7:00 PM news, again just in time for the May ratings sweep.

On June 12, 1975, Bonds announced that he was moving to WABC-TV in New York City at the end of August, for a salary reported to be somewhere between $120,000 to $150,000. But only eleven months after taking the WABC anchor job, Bonds returned to Detroit and was glad to be back. The New York City media market was so huge that Bonds made little more than a blip in the ratings, so his contract was not renewed. Bonds returned to the WXYZ-TV Action News Team to co-anchor with John Kelly.

***

Bonds was at the top of his game. His agent negotiated a multiyear contract which began at the $200,000 mark. Bonds was the highest paid newsanchor in town. Despite his tarnished history at Channel 7 for excessive absences from the newsroom and bad publicity for two alcohol-related incidents, Bonds remained the number one anchorperson in the Detroit media market.

In the Detroit Free Press' annual readers' poll taken in September of 1981 for Detroit's most popular local anchorperson, Bonds netted 1,929 votes of over 7,000 ballots cast. Mort Crim of Channel 4 was in second place with 676 fewer votes. No other Detroit anchorperson could come close to Bonds popularity with the general public.

When Bonds withdrew from the local Emmy Awards competition in 1980, he called the awards "ludicrous, insulting, and a sham." Bonds was the only news celebrity to publicly withdraw from the televised event. He told WXYZ-TV vice president and general manager Jeanne Findlater, "I am not going to play the part of an Eight Mile Road whore because of the pimping that's going on for these little statuettes."

Bonds pointed out that unqualified people outside the television news community (actors, sports celebrities, advertisers, and academics) chose the nominees, and a Channel 2 executive was chairman of the nominating committee. Channel 2 received 37 nominations, Channel 7 received 19, and Channel 2 received just 16. There was a clear conflict of interest.

After the televised event, The Detroit Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences announced that the Detroit Emmy Awards would no longer be broadcast because of public controversy and bad ratings. Such was Bill Bonds' influence over the local media scene.

But Bonds was about to be brought low with the death of his oldest daughter. On December 16, 1981, tragedy struck the Bonds' family when Joan Patricia Bonds (18), home for winter break from Michigan State University, was killed in a head-on collision with another car on a winding stretch of Commerce Road in Orchard Lake. Her Volkswagen Rabbit was hit by a Mercury driven by Russell William Brown (34), when it was believed his car crossed the center lane. Brown suffered a concussion and was treated at Osteopathic Hospital and released. Both cars were totalled.

The Orchard Lake Police investigation revealed that both Joan Patricia Bonds and Russell William Brown were legally drunk when the accident occured. Brown's blood alcohol level was 0.19 and Joan Bonds' blood alcohol level was 0.17. In Michigan, a person is legally drunk with a level of 0.10. Drunken driving was a misdemeanor carrying a maximum penalty of 90 days in county jail and/or a $500 fine. Brown was charged with the head-on crash.

Bill Bonds was off the air for almost three weeks after the death of his daughter before returning to anchor Channel 7's 6:00 PM broadcast. At the end of the hour-long newscast, Bonds, holding back tears, thanked the many viewers who had called or written to express their condolences.

Bonds' health began to deteriorate in 1982. He complained his back and legs began to give him problems and sidelined him from December until February. WXYZ-TV spokesperson told the press that Bonds was on special assignment to downplay his absence.

On October 15, 1983, Bonds (50) collapsed in Metro Airport just before his scheduled flight to Tokyo to cover Mayor Coleman Young's tour of Japan. He complained about acute stomach pains and difficulty standing up and was taken to Wayne County General Hospital and held for tests and observation for several days. He missed his trip. Ruth Whitmore, spokesperson for Channel 7 said, "(Bill) needs rest. We won't push him to travel." Medical tests indicated that doctors found no heart damage. Bonds returned to the news desk the following Wednesday.

On Friday, February 3, 1984, Bonds was hospitalized for exhaustion. His physican said his patient was suffering from persistent problems with his lower legs. Numerous station sources believed Bonds' recent round of health problems were the result of grief over the death of his daughter. Others believed he was being treated for drug and alcohol dependency. After a month of recuperating, Bonds returned to the anchor desk.

Ten months later, Bonds' wife Joanne Sipsock (47) filed for divorce. They were married for 24 years and had four children: Joan [deceased in 1981], John, and twin daughters Krissy and Mary. By all accounts, it was a messy divorce. Some unspecified time later, Bonds announced that he had a "significant other" named Karen Field, who was a manufacturer's sales representative. His health and general disposition improved.

***

Bill Bonds' most notorious moment to date of his broadcasting career happened on Friday, July 14, 1989. At the end of his 11 PM broadcast where he was noticeably slurring his words, Bonds challenged Mayor Coleman Young to a charity boxing match to benefit the Detroit Public Schools athletic program. He proposed a one-round showdown at the Palace of Auburn Hills on August 11th during halftime at the Detroit Pistons' charity all-star exhibition game.

|

| Mayor Coleman Young and Bill Bonds eating coneys downtown. |

Bonds suggested that both he and Mayor Young put up $10,000 each to donate, along with the proceeds of the exhibition basketball game, to help restore varsity sports in Detroit.

Local media wags dubbed the fight "The Showdown in Motown" and "Malice at the Palace." One reporter wrote,"This is a way for Bill Bonds and Detroit Mayor Coleman Young to settle the accumulation of small but distracting grievances between them."

Then, Bonds was absent without official leave from his Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday night broadcasts. Station manager Tom Griesdorn arranged an impromptu news conference on Thursday to end speculation. "Bill called me earlier today and asked for some time off, vacation and personal leave, and we granted that request."

Griesdorn refused to comment on the barage of questions that followed. Usually, he answered "No comment!" or "That's none of your business." The entire incident was a public relations disaster for Channel 7.

Some Channel 7 staffers, pleading for anonymity, leaked the news that Bonds asked the station for help and some time off to enter an unidentified medical facility for an unspecified treatment. Three weeks later, Griesdorn confirmed WXYZ-TV's worst-kept secret, "Bill Bonds revealed that he has a problem with alcoholism, and he has checked himself into a California clinic for treatment."

After drying out, Bonds returned to the newsdesk in August. At the end of his 6 PM newscast, he confessed publicly that he was an alcoholic, but a sober one ready to do the news once more. Maybe this time he would win his battle over the bottle. For now, he would have to be satisfied with winning over the hearts of many Detroiters, who were all too familiar with alcohol addiction in their families.

***

In 1991, WXYZ-TV signed Bonds to a long term contract (5 to 7 years) for a million dollars a year prompting many people to wonder why he was worth so much considering his checkered history at the station. The answer was simple. Advertising rates were dependent on ratings achieved. Bonds was a ratings generator for the station for most of his long career. He appeared twice daily anchoring the news, he hosted prime time specials, anchored local election coverage, and made countless public appearances for the station. Being number one in his media market for twenty consecutive years earned Bonds the nickname "The Million Dollar Man."

|

| Always impeccably dressed on camera, Bill often wore Levis or shorts at the newsdesk. |

Bonds kept his nose clean until an incident in April 1994 when his briefcase did not make it through security screening at Metro Airport. A pair of brass knuckles was detected at the inspection checkpoint. Although possessing a weapon was illegal in Michigan, the Wayne County Assistant Prosecutor said he determined there was "No criminal intent in this case. The brass knuckles were accidently possessed."

Bonds told authorities "I own four briefcases and grabbed the wrong one. Someone gave the brass knuckles to me as a gag-gift at work. I threw them in a briefcase and forgot about them." The knucks and the briefcase were turned over to airport police to be destroyed.

Once again, Bonds' celebrity status saved him considerable legal fallout, and he was able to catch his flight to New York City. Critics familiar with Bonds' background wondered, "How many bites at the apple can one person take?" Detroiters were about to find out.

***

On Sunday, August 7, 1994, Bonds was arrested on suspicion of drunk driving following a twenty-mile pursuit. A 1991, teal-blue Jaguar XJS was veering erratically on northbound Southfield Freeway. A driver called 911 and reported the incident. The sportscar swerved west onto I-696 before exiting at Orchard Lake Road. At a red light, a red Ferrari pulled up next to the Jag and revved its engine. Both cars peeled their tires when the light turned green, the Ferrari pulled out in front leaving the Jag fishtailing in its dust.

Another witness called 911 reporting that he saw Bill Bonds pull into a gas station to fuel up. On the way out of the station, Bonds smacked his car into a lamppost and then verred onto Indian Trail coming within inches of colliding with another car. As Bonds turned west down Commerce Road, five police cars closed in on him. It was soon discovered that the Jag did not belong to Bonds. It was a Channel 7 company car that he was joyriding in.

The Orchard Lake Police used video and audiotape to record Bonds as he performed a sobriety test while seated in the car. He declined a breathalyzer test and a standing sobriety test, citing neurological problems from an unspecified orthopedic condition--an excuse he had used successfully before.

Police later obtained blood samples after the arrest which showed Bonds' blood alcohol was 0.21%--twice the legal limit. He was jailed for twelve hours until his second wife Karen posted bail. If convicted, he faced six months in jail, a $500 fine, a suspended license for six months, and community service. Two days later, Free Press reporter Susan Ager wrote, "Bonds is captivating because he is an exquisitely flamboyant failure at self-improvement."

This incident threatened to end Bonds' reign at the summit of Detroit television news. Station manager Tom Griesdorn announced to the press that Bonds "asked for and was granted a personal leave of absence, the duration of which will be determined by the outcome of the allegations." Bonds remained in seclusion at his Union Lake home.

On August 11, 1994, Bonds was suspended from WXYZ-TV by Griesdorn pending "successful completion of alcohol treatment in Atlanta at Talbott-Marsh Recovery Center until his health is up to speed. The station wishes Bill Bonds every success as he sets about combating his addiction to alcohol once and for all." This was Bonds' third attempt at alcohol rehabilitation.

On December 2, 1994, Bonds pleaded guilty to a reduced charge of driving with an unlawful blood alcohol level; the driving under the influence charge was dismissed. His sentence included 12 months of supervised suspension with a 270-day license suspension, continued outpatient alcoholism treatment, a $1,115 fine exclusive of court costs, and attendance three times a week at Alcohol Anonymous meetings. If he did not comply with all stipulations of his sentencing, he would be jailed for 90 days.

On January 11, 1995, WXYZ-TV fired Bonds. "We've simply decided to hold our head high and face the future without Bill Bonds," said General Manager Griesdorn. "This is not a personal decision but simply a judgement about what is best for the station's long-term interest." Bill Bonds' long career with WXYZ-TV was over. Despite attempts to regain his footing at other Detroit media outlets, the old magic was gone. He was reduced to being a pitchman for Turf Builders and Gardiner-White Furniture.

|

| A collage of photos from Bill Bonds' funeral. |

On December 13, 2014, Bill Bonds died of a heart attack at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Pontiac, Michigan at the age of eighty-two. His visitation was on December 18th at Lynch & Sons Funeral Home in Clawson, with a funeral mass held at Holy Name Catholic Church in Birmingham the next day.

Despite Bonds' human failings, many thousands of working-class Detroiters admired him for his pluck, bluntness, and tenacity. He will be remembered for his on-air swagger, piercing gaze, defense of the underdog, and his authoritative delivery of the news.