|

| Edsel Ford |

Unlike Edsel Ford's children, Edsel was not born in the lap of luxury. His father and mother, Henry and Clara, lived on the cusp of poverty while Henry invested every spare cent he could earn at the Edison Illumination Company in Detroit to develop his horseless carriage made of four bicycle wheels, a carriage frame, a tiller steering lever, an upholstered bench seat, and a two-cylinder, four horsepower, chain driven engine. He called his contraption the Quadricycle.

On June 4th, 1896 at the age of thirty-two, Henry Ford took the first of many test drives. Although he had no memory of it, his four-year-old son Edsel took his first ride in a self-powered vehicle. Ford quit his job at Edison in 1899 to focus on building automobiles and formed the Detroit Automobile Company. Two years later [1901], he formed the Henry Ford Company, and two years after that, he founded the Ford Motor Company [1903]. While Henry struggled to dominate the early automobile business, he and Clara lived in twelve different places before he had Fair Lane manor built in 1913 through 1915. Edsel was in his early twenties when the mansion was completed.

|

| Ford's original quadricycle |

Although his parents doted on him, Edsel's home life was anything but stable. As a child, Edsel went to a private grammar school in Connecticut and then attended Detroit University School, a local private college preparatory school. The family company was the most stability Edsel had in his young life. He grew up with the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) and would hang around the design and pattern shops on his school vacations where he became acquainted with master model-maker and Ford engineer Charles "Cast Iron Charlie" Sorensen. Sorensen, who over the course of his forty-year career with Henry Ford and his company, would become young Edsel's lifelong friend and mentor.

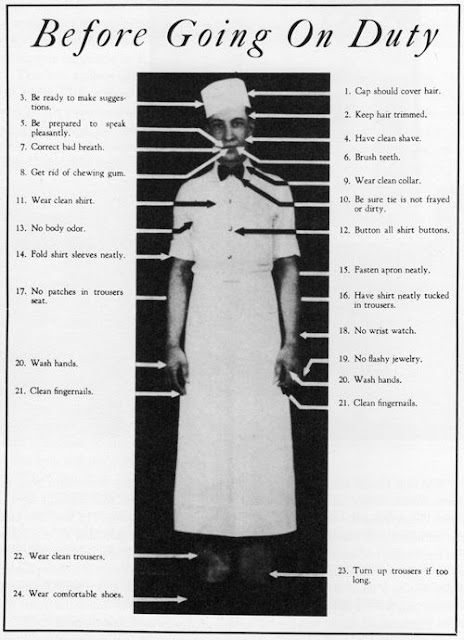

Rather than take the next step into a university education, Edsel made the decision to enter the family business at age eighteen. I'm sure his father prompted him to make this decision. Henry Ford was a no-nonsense, self-made man who was distrustful of university educated types. All of the early, key people in the company had come up the hard way like Ford did. But rather than break Edsel in on the grimy foundry floor or the assembly line, Ford sent his son to work in the business end of the operation in financing. Edsel never dressed less than sartorial [well-tailored]. His personal taste in clothing was impeccable in stark contrast to those he worked with, but his work ethic and integrity soon won over most people.

In 1915, James Couzens resigned as secretary/treasurer of FoMoCo in protest of Henry Ford's public, pacifist statements and pro-German sentiments while on a European "peace ship" mission. Edsel was the heir apparent and succeeded Couzens becoming the company's first finance director--a title made especially for Edsel. His father did not like titles for his excutives and preferred they be called simply "Ford Men." Henry Ford felt he could utilize and control them better if there was ambiguity in the management ranks.

The company's great chain of being had room for only one person at the top--Henry Ford. Despite that, Henry stepped aside in 1919, and Edsel became the president of the company while Henry remained on his company's board of directors. The elder Ford held over 50% of the company's stock. That was his trump card. With his son, Henry began a secret project which resulted in the development of a small block V-8 engine and the Model A, which saved the company from bankrupcy and the General Motors Corporation whose Chevrolet division was eating away at FoMoCo's dominance in the low priced market.

Here is where the plot thickens: A year after Edsel's management promotion, he married Eleanor Lowthian Clay [19], a socialite who was the niece of J.L. Hudson, the department store founder. The newlyweds did not want to live at the Fair Lane manor with Edsel's parents. The elder Fords were crestfallen. They had Fair Lane built especially with the thought of keeping Edsel under their wing. The manor was built near the banks of the Rouge River with a built-in swimming pool, a game room, a bowling alley, a billiards room, a boathouse, and a riding stable all designed with their son in mind.

According to Charles Sorensen in his autobiography My Forty Years with Ford, "Father and mother wanted to keep their only son close to them and guide his every thought.... Like all normal young people, Edsel wanted to be on his own to see and experience the world." Important people began to admire and respect the young executive which rankled his father who was jealous of anyone who seemed to wield influence with his son. "Henry Ford's greatest failure was expecting his son to be like him," Sorensen wrote. "Edsel's greatest victory, despite all obstacles, was in being himself."

The Edsel Fords made their first home in Detroit's Indian Village neighborhood on Iroquois Street where all four of their children were born: Henry II [1917], Benson [1919], Josephine [1923], and William Clay [1925]. In 1929, the Edsel Fords moved to Gaukler Point in Grosse Pointe with 3,000 feet of shoreline on Lake St. Clair and a walled-off, massive estate. Grosse Pointe was where wealthy and influential Detroiters lived, some residents with ties to Ford's arch competitor General Motors.

|

| Henry II [the Deuce], Benson, Josephine, William Clay |

The Henry Fords were nonsmoking teetolalers who disapproved of rumors of Edsel's riotous living, like attending cocktail parties and joining a country club. Edsel was being surveilled by Harry Bennett's men. It was being reported that Edsel was being corrupted by alcohol. The Edsel Ford's always kept a fully stocked bar in their home, even during Prohibition. Henry was distrustful of Edsel's new friends in Grosse Pointe, but Edsel chose his own friends and adopted a modernist sensibility apart from the fundamentalism of his parents.

With the help of his wife Eleanor, Edsel educated himself in the arts and literature and became an art collector. In contrast, Henry Ford was raised a farm boy with a sixth grade, rural education who was fond of saying, "A Ford can take you anywhere, except into society." He was wrong. This was the beginning of a serious riff between Edsel and his father.

Henry Ford put his controversial henchman Harry Bennett on Edsel's neck to disabuse him of the notion that he was actually the president of FoMoCo. It was clear to everyone that Edsel wore the mantle, but his father was the power behind the throne. Edsel had the title but not the scepter that went with it. Sorensen noted that "Henry could not let go, and Edsel did not know how to take over."

|

| Harry Bennett with Henry Ford |

Edsel always deferred to his father's edicts and allowed him to trample on his dignity, first with the company and later by tampering with the private lives of Edsel's family and inlaws, usually through the efforts of Harry Bennett. The elder Ford was primarily responsible for crushing his son's spirit. Ford believed his son was weak, and he blamed himself for overprotecting Edsel with the "cushion of advantage." For the sake of the company, Henry felt he needed to toughen the boy up.

Of his many transgressions against his son, the elder Ford found fault with anything Edsel wanted to do to make FoMoCo more competitive. Edsel wanted to modernize the company with college-educated executives, but Henry would not stand for that. He wanted his executives to start at the bottom and work themselves up the corporate ladder.

In 1919, Henry Ford bought the Dearborn Independent newspaper. At his personal direction, Ford instructed his editor William Cameron and his FoMoCo administrative assistant Ernest Liebold to begin a journalist rampage against the Jews and the International Banking Conspiracy. Edsel had many Jewish friends and implored his father to shut down his antisemitic screed. To compound matters, Henry Ford required his dealers to include a copy of the newspaper in every new vehicle sold resulting in lost sales. American Jews would not be caught dead buying a Ford car.

In 1922, many of the articles were compiled into a book called The International Jew, which sold well in the United States and found an enthusiastic audience in Germany. Thirty-three-year-old German militant Adolf Hitler kept a well-read, dog-eared copy of the book on his desk and had a signed photo of Henry Ford on the wall of his office. After losing a very public and expensive lawsuit, Henry Ford was forced to shut down the paper in 1927, but the damage had been done, much to the personal embarrassment of Edsel and Eleanor.

Another tramatic event for FoMoCo was the Battle of the Overpass on May 26, 1937 between underworld thugs hired by Harry Bennett and the United Auto Workers (UAW), who were distributing pro-union literature on the Miller Road pedestrian bridge leading into the Rouge Plant. Detroit News photographer James J. Kilpatrick, snapped a few quick photos and jumped into a waiting car to avoid a beating and a busted up camera. The photos appeared in the evening edition of the Detroit News, and by morning, it was picked up nationally and internationally.

Edsel was struggling with his health and wanted the company to settle the contract which had already been settled at General Motors and Chrysler Corporation. Henry Ford wanted to dig in and bust more heads. He gave Harry Bennett free reign and unlimited funds to break the UAW, which Ford believed was communist-inspired socialism. Clara Ford summoned Charles Sorensen to Fair Lane to ask, "Who is this [Harry] Bennett, that has so much control of my husband?" She did not like what she heard from Sorensen.

Clara Ford threatened her husband Henry with divorce and selling off her FoMoCo stock if a contract settlement was not reached immediately. That got the old man's attention, but Edsel was in no condition to negotiate, so in a stroke of twisted irony, Ford had Harry Bennett represent the company and settle the contract.

|

| Clara Bryant Ford |

In another blunder of epic proportions, Henry Ford was awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle for his 50th birthday in 1936 as a token of Adolph Hitler's admiration. The medal made of gold was replete with four Nazi swastikas. Mindful of its propaganda value, Hitler's two German representatives stood on each side of Henry Ford with the medal hanging prominately around his neck and had a publicity photo taken. The photo appeared in newspapers worldwide. Ford appeared sympathetic with the Nazi cause in Europe, prompting many Americans to again question whose side Ford was on and consequently losing FoMoCo business. Edsel Ford pleaded with his father to denounce Hitler publicly, but he would not relent.

Edsel was friends with Democrat President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who Henry Ford despised as a socialist. When President Roosevelt asked Edsel Ford to get behind the World War II war effort, Edsel agreed to put the might of FoMoCo behind the war effort and vowed to do anything he could. Henry did everything he could to undermine the Willow Run bomber project fearing the government would take over his company, but after Hitler invaded Poland, Ford was forced to admit that Hitler was a dictator and enemy of the United States.

Along with plant manager Charles Sorensen and architect Albert Kahn, Edsel Ford dedicated the last years of his life to designing and constructing the largest bomber plant in the world which became the cornerstone of the United States' Arsenal of Democracy. The stress and strain of the job and the harassment by his father and Harry Bennett finally caught up with Edsel. In January of 1942, Edsel was operated on for stomach ulcers. The elder Ford believed his son only needed to "change his way of living." He thought his chiropractor could cure him. When surgeons opened Edsel up, they discovered incurable metastatic stomach cancer. Edsel Ford hung on for eighteen months but died at one-ten a.m. on May 26, 1943 from cancer and undulant fever brought on by drinking unpasteurized milk from Ford Farms.

|

| B-24 Liberator Bomber |

Although Edsel did not live to see the end of World War II, his boast of producing a complete B-24 bomber every hour was achieved. The Willow Run Bomber Plant and adjoining airport represent Edsel's greatest achievement against overwhelming odds where the stakes could not have been higher. His father's fame plateaued after the construction of the Rouge Plant; Edsel's fame rests squarely upon the miracle of the B-24 Bomber Plant. The elder Ford may have put America on wheels, but his son was instrumental in making the world safe for democracy and preserving the American way of life.